Moving Beyond Identity (Part 2)

Intersectionality and Practices of Solidarity in Organizing

In the first two essays of my series, Practices of Liberation: Essays on Transformative Organizing, I introduced foundational concepts like self/co-regulation, positionality, relational accountability, transformative organizing, identity politics, and intersectionality. These tools help me counter burnout and build sustainable movements in an era of mounting authoritarian threats.

My goal is to share concepts, language, and practices foundational for working together toward universal liberation. While I strive to use accessible language, I value the specificity that certain terms provide. Words matter! They help us navigate complex dynamics in organizing groups. Throughout this series, I’ll define key terms within the text and offer a glossary at the end for easy reference.

Let’s Start With A Story

A recent anecdote about my own stumbling practice with identity and intersectionality: Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ) organizes white people to engage in anti-racist work, answering the call of Black civil rights leaders and groups like the Combahee River Collective. While its mission is clear, its impact can be more complex in practice.

Jump to Glossary

Two BIPOC friends of mine recently expressed feeling excluded from SURJ’s activities despite its coalition work with BIPOC groups. They felt invisibilized in meetings where the focus was on "white people" and struggled with discomfort around its demographic-specific premise. Meanwhile, some white organizers I know feel uneasy about organizing solely within their demographic, yearning for multi-ethnic organizations instead.

Post-election, SURJ has ramped up their onboarding and training sessions with national calls and local "Gear Up" circles to bring more people into their work. It was hard for me to decide whether or not to host a circle, knowing that these friends of mine might not feel good about joining even if I invited them.

Ultimately, I decided to do it. As a white organizer, I see the continued need for white people to confront racism within our own communities, especially given the election results. But I also struggle with the idea of exclusionary organizing. This tension has pushed me to ask: How do we balance the necessity of demographic-specific work with the urgency of building inclusive coalitions? How do we practice relational accountability when our efforts to center marginalized voices feel at odds with broader solidarity?

These questions remind me that organizing is an iterative process, requiring repeated recalibration.

I only have partial answers right now. Demographic-specific work, like SURJ organizing white people for racial justice, seems important for addressing specific roles and responsibilities in dismantling oppression. White people organizing other white people can lessen the burden on BIPOC communities and focus the labor of anti-racism where it is needed most. At the same time, building diverse, inclusive coalitions is critical for long-term systemic change. Solidarity across lines of race, gender, class, and other identities strengthens movements and ensures that solutions reflect the needs of all communities.

The balance lies in recognizing when each approach is most effective. Demographic-specific work can serve as a foundation, preparing individuals by fostering critical awareness of systemic inequalities, developing skills for allyship, and equipping them with strategies to engage meaningfully in broader coalitions. It can also exist in tandem with inclusive coalitions, as long as there is clear communication and accountability between groups—like when SURJ prioritizes educating white people about systemic racism but also maintains active partnerships with BIPOC-led organizations, ensuring alignment on shared goals.

Centering marginalized voices is a cornerstone of intersectionality, but when it feels exclusionary or siloed—if connections aren’t maintained—it can fracture solidarity. These moments require revisiting priorities and practices. Relational accountability can serve as a bridge. It invites open dialogue about tensions, ensuring that concerns can be addressed constructively rather than dismissed or ignored. Demographic-specific groups can actively solicit feedback from marginalized communities about their work’s impact and adapt their strategies accordingly. Inclusive coalitions can create spaces for processing harm or misunderstanding, fostering trust and mutual respect.

Identity Politics and Relational Accountability

Intersectionality offers a way to honor identity without collapsing it into essentialism or identitarianism. It recognizes that identity is important but doesn’t define who someone is in static or predictable ways. Nor does it call for a politics based solely on identity, which can impose rigid structural categories onto individuals, often distorting their politics or erasing their complexities.

Kimberlé Crenshaw highlights that “the struggle over which differences matter and which do not... raises critical issues of power.” This observation ties directly to the importance of relational accountability, as understanding and addressing these differences can help to foster inclusive and equitable movements. It also underscores the necessity of examining power dynamics within organizing spaces to ensure that collective goals are not undermined by internal exclusions or oversights. Ignoring differences within groups often contributes to internal exclusions and marginalizations. She suggests that “intersectionality offers a way of mediating the tension between assertions of multiple identity and the ongoing necessity of group politics.” By acknowledging and grounding both our differences and our commonalities, we strengthen our movements.

This is where relational accountability becomes essential. Relational accountability means shared responsibility for building and maintaining trust and integrity in relationships. In transformative organizing, this looks like centering care and inclusivity, addressing harm constructively, and committing to mutual learning and humility. It’s about recognizing that solidarity requires ongoing effort and adaptability.

Using an intersectional lens often leads us to re-center marginalized voices in our movements, which I think is necessary and important. Deference politics—the practice of prioritizing the voices of marginalized groups based on their identities—can help correct historical exclusion and silencing. As bell hooks wrote in Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, “Margins are sites of creativity and resistance.” Prioritizing perspectives from the edges of our groups allows movements to challenge oppressive structures more effectively.

But deference politics also has its limits. Taken to extremes, it can push conflict underground and stifle collective problem-solving. I’ve seen this dynamic play out in organizing spaces where deference has become a barrier to relational accountability. For example, centering marginalized voices without creating pathways for shared responsibility can sometimes allow dominant identities (men, white people, academics) to opt out of the hard work of restorative justice. Or it can reinforce competitive victimhood or tokenize individuals who are already carrying the burdens of marginalization.

In transformative organizing, relational accountability complements intersectionality, ensuring that everyone—regardless of positionality—is held to the group’s shared values and goals. It means fostering a culture of dialogue, shared learning, and collective repair.

Although identity politics sometimes act as a fetter on genuine multiracial/multicultural alliances, I believe it has also enriched our conception of class. Indeed, there are many serious scholars—I count myself among them—trying to understand how various forms of fellowship, racial solidarity, communion, the creation of sexual communities, and nationalism shape class politics and cross-racial alliances. We are grappling with how self-love and solidarity in a hostile context of white supremacy, the embrace of certain vernaculars, can be expressions of racial and class solidarity, and the way class and racial solidarity are gendered. […]

After all, the analyses, theories, visions emerging from the black liberation movements, the Chicano and Asian American movements, the gay and lesbian movements, the women's movements, may just free us all. [...] Attempts to "transcend" (read: outgrow) our race and sex does not make for a unified working class. What does is recognition of the multiplicity of experiences and perspectives and a willingness to struggle on all fronts—irrespective of what "the majority" thinks. Recognizing the importance of environmental justice for the inner city; the critical role of antiracism for white workers' own survival; the necessity for men to fight for women's rights and heterosexuals to raise their voices against homophobia. It's in struggle that one learns about power and how it operates, and that one can imagine a different world. And it's in struggle, not in the resurrection of [Enlightenment] ideas that have also provided the intellectual justification for modern racism, imperialism, and the traffic of human beings, that we must begin to develop a new vision. Robin D.G. Kelley, Identity Politics and Class Struggle, 1997

Liberal Identity Politics and Elite Capture

Identity politics has been co-opted and weaponized by liberalism in ways that undermine its revolutionary potential. For instance, liberal frameworks often emphasize symbolic representation—such as increasing diversity in corporate leadership or political offices—without addressing the underlying systems of oppression. This co-optation prioritizes surface-level inclusivity over transformative change, enabling powerful elites to maintain the status quo while appearing progressive. Additionally, the rhetoric of identity has been used to marginalize leftist critiques, as seen when corporate and political leaders use their identity markers to deflect accountability for policies that perpetuate inequality or environmental degradation. Asad Haider, in Mistaken Identity, critiques the way liberal identity politics often fragments movements and prioritizes symbolic representation over systemic change. Olúfémi Táíwò calls this phenomenon “elite capture,” where the rhetoric of identity is hijacked by those in power to reinforce their dominance.

Crenshaw observes that “the embrace of identity politics... has been in tension with dominant conceptions of social justice.” Race, gender, and other identity categories are often treated as “intrinsically negative frameworks in which social power works to exclude or marginalize those who are different.” This misinterpretation allows for the manipulation of identity politics to serve neoliberal agendas.

We’ve seen this dynamic play out in real time, from the rise of leaders like Margaret Thatcher and Condoleezza Rice, who wielded power to perpetuate systems of oppression, to the Democratic Party’s misuse of identity politics to undermine leftist organizing, strategies, candidates, and movements. This is possibly most obvious in the betrayal of Bernie Sanders’ wildly popular presidential campaign and platform, and the well-fleshed-out Green New Deal.

Identity alone is no guarantee of a liberatory politics. As Barbara Smith and the Combahee River Collective remind us, true intersectionality is rooted in anticapitalism and anti-imperialism. So when politicians like Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris claim their identity markers as sufficient reasons to elect them—while also campaigning on free market economics, military dominance, fracking, and walking back promises on universal healthcare—they cleanse their reputations using their identities as women and, in Harris’ case, as a woman of color. This is not intersectionality.

On the global stage, identity is also weaponized in right-wing culture wars. If “lean in” feminism can trick some of us, some of the time, the rhetoric and policies of conservative and far-right female politicians make the twisting of identity even more obvious. White supremacist and nationalist “Identitarian” movements have used distorted versions of identity to sow division and justify harm. These challenges make it even more critical to practice a dynamic intersectionality—one that balances acknowledgment with systemic critique and relational accountability.

Weaponized Identity Politics and the Need for Intersectional Solidarity

Identity politics, as a concept rooted in systemic analysis, has often been distorted and weaponized against grassroots movements for justice. We see this in the way Black Lives Matter activists are labeled as "divisive" or "violent" for challenging state-sanctioned violence against Black people. Similarly, during the Standing Rock protests, Indigenous water defenders were painted as radicals or anarchists (as if those are bad things), with their calls to protect sacred land dismissed as fringe environmentalism.

These narratives rely on shallow and intentionally distorted readings of identity to delegitimize the collective, intersectional demands for justice. This isn’t confined to the U.S. In global Palestine solidarity movements, activists have faced similar distortions, where critiques of Israeli state violence are reframed as antisemitism. These examples highlight why intersectionality isn’t just about understanding identities but about addressing systemic forces—capitalism, imperialism, racism—that co-opt and twist identity to suppress collective action.

Reclaiming intersectionality means grounding our solidarity in shared struggles while resisting attempts to divide us through manipulations of identity.

Practical Applications of Intersectionality

Intersectionality is not just a theoretical framework—it’s a practice. As discussed earlier, it offers a lens for understanding how overlapping systems of oppression interact and shape lived experiences. This conceptual groundwork leads us to the question: How do we apply intersectionality in organizing spaces to foster systemic change? Transitioning from theory to action, we can explore practical tools and strategies that operationalize these ideas in transformative ways. Transformative organizing applies this lens through actionable tools like:

Asset and Power Mapping: Identify strengths, systemic barriers, and opportunities for intervention.

Balanced Narratives: Combine personal stories with structural analysis during meetings to ensure both are heard and contextualized.

Community Agreements: Establish shared expectations for engagement and accountability.

Trauma-Informed Practices: Create spaces for processing harm constructively without derailing collective work.

Guiding Frameworks: Use resources like the Jemez Principles and SisterSong’s Reproductive Justice framework to guide coalition-building.

In the context of antiracism, recognizing the ways in which the intersectional experiences of women of color are marginalized in prevailing conceptions of identity politics does not require that we give up attempts to organize as communities of color. Rather, intersectionality provides a basis for re-conceptualizing race as a coalition between men and women of color. […] Intersectionality may provide the means for dealing with other marginalizations as well. For example, race can also be a coalition of straight and gay people of color, and thus serve as a basis for critique of churches and other cultural institutions that reproduce heterosexism. Kimberlé Crenshaw, Mapping the Margins, 1991

And Lastly, Our Call to Action

A dynamic intersectionality requires flexibility, humility, and a commitment to systemic change. It challenges us to center marginalized voices without tokenizing them; critique systems without descending into identitarianism; and practice relational accountability in all aspects of organizing.

As you reflect on these ideas, I encourage you to ask yourself (and share in the comments!):

How do you navigate the balance between demographic-specific and inclusive organizing in your work?

When have deference politics helped or hindered your efforts?

By applying intersectionality as a dynamic, relational practice, we can build movements that are inclusive, imaginative, and deeply transformative. Together, we can work toward a future that prioritizes universal liberation—one rooted in care, creativity, and collective accountability.

Resources/Links

Robin D.G. Kelley, Identity Politics and Class Struggle, 1997

Katie Halper interviewing Barbara Smith, Robin D. G. Kelley, and Norman Finkelstein on Identity Politics, 2023

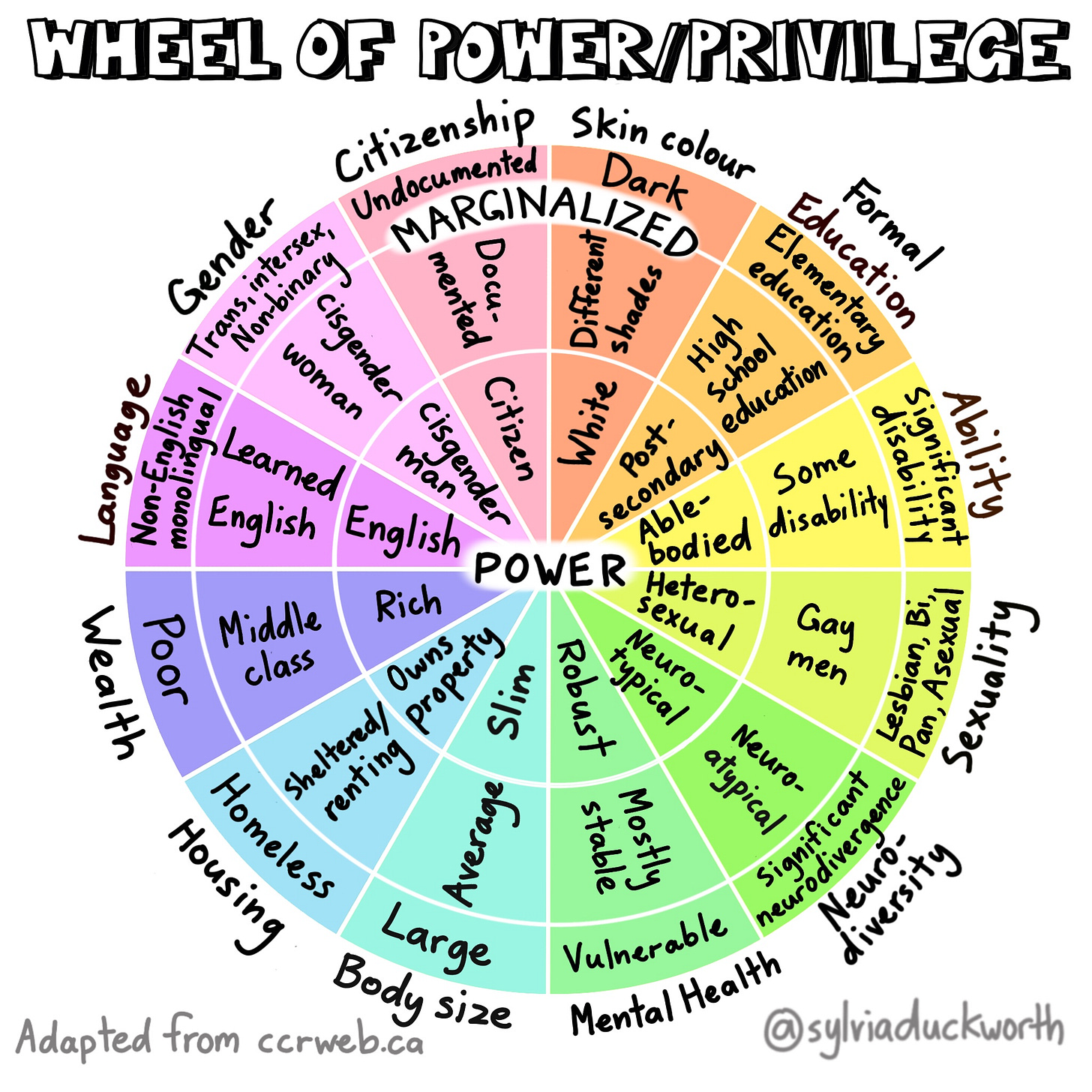

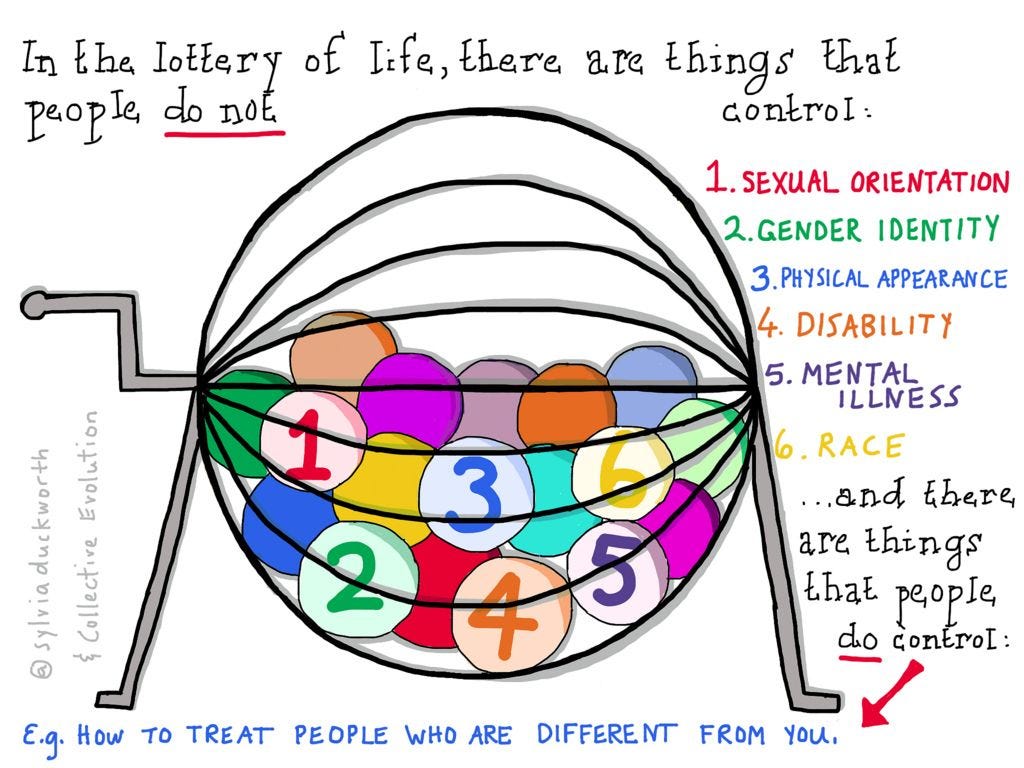

Sketchnotes: https://sylviaduckworth.com/

Glossary

Back to top

Anti-Capitalism: Opposition to systems prioritizing profit over people, emphasizing equitable resource distribution and workers’ rights.

Anti-Imperialism: Resistance to political, economic, or cultural domination by one nation over another.

Deference Politics: The practice of prioritizing the voices and leadership of marginalized individuals based solely on their identities. While intended to correct historical exclusion, over-reliance on deference politics can stifle critique and relational accountability.

Elite Capture: When powerful groups hijack social justice rhetoric to maintain dominance rather than dismantling oppression.

Essentialism: The belief that certain characteristics, behaviors, or identities are innate, fixed, and universal. In the context of social justice, essentialism often oversimplifies identity categories, ignoring the diversity and complexity within them.

Identity Politics: Political analysis and action based on the experiences and needs of marginalized groups, first articulated by the Combahee River Collective.

Identitarianism: A rigid focus on identity that reduces individuals to fixed categories, often at the expense of systemic analysis or coalition-building. Identitarianism is currently manifesting as white supremecist, nationalist movements.

Intersectionality: A framework coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw to analyze how overlapping systems of oppression shape lived experiences and systemic barriers.

Structural Intersectionality: The ways in which overlapping systems of oppression—like racism, sexism, and economic inequality—compound to create unique barriers for individuals within marginalized groups.

Political Intersectionality: The recognition that individuals’ identities often place them at the intersection of multiple political struggles, requiring movements to address overlapping and sometimes conflicting needs and priorities.

Liberal/Liberalism: A political philosophy that emphasizes individual rights, free markets, and representative democracy. In the U.S., liberalism often refers to centrist policies that focus on reforming, rather than dismantling, systemic inequalities.

Liberal Identity Politics: A form of identity politics co-opted by liberalism, focusing on representation over systemic change. Identity is used to uphold capitalism, rather than systemic change and universal liberation.

Positionality: The recognition of how an individual’s social identities (e.g., race, class, gender) and power dynamics shape their perspective, experiences, and interactions within systems of oppression and privilege.

Relational Accountability: Shared responsibility for maintaining trust, care, and integrity in relationships, ensuring solidarity and mutual respect.

Self/Co-Regulation: Balancing emotional responses for individual or collective productivity in organizing spaces.

Transformative Organizing: A framework for social change that integrates systemic critique, relational accountability, and care to build sustainable, inclusive movements aimed at dismantling oppression and creating liberatory alternatives.