Moving Beyond Identity (Part 1)

Intersectionality and Practices of Solidarity in Organizing

In the first essay of my series, Practices of Liberation: Essays on Transformative Organizing, I introduced foundational concepts like self/co-regulation, positionality, relational accountability, and transformative organizing. These tools help me counter burnout and build sustainable movements in an era of mounting authoritarian threats.

My goal is to share concepts, language, and practices foundational for working together toward universal liberation. While I strive to use accessible language, I value the specificity that certain terms provide. Words matter! They help us navigate complex dynamics in organizing groups. Throughout this series, I’ll define key terms within the text and offer a glossary at the end for easy reference.

What Am I Even Talking About?

In this second installment, I explore intersectionality as a powerful framework and practice that serves as a foundation for transformative organizing. It provides tools for honoring identity while resisting liberal identity politics, essentialism, and identitarianism, helping us navigate the tension between recognizing difference and building solidarity.

Jump to Glossary

How can we honor identity and use an intersectional lens without descending into liberal identity politics or essentialism? How do we avoid deference politics that undermine relational accountability, mutual respect, and, ultimately, our goals of systemic change? And how do we see and name the manipulations of identity politics that are so pervasive in our culture?

These questions feel urgent to me because, in my world, they are ever-present and often painful. As we build movements and activate members, we inevitably encounter people at different stages of political awareness, emotional dexterity, and agreement. Disagreements are inevitable, but grounding ourselves in shared values and language can help us navigate these differences constructively without losing sight of our collective goals.

In my own organizing work, I’ve seen how identity politics and solidarity are deliberately weaponized—not just to discredit individuals, but to undermine broader movements for justice. This weaponization targets structural identities like race or gender—the familiar terrain of identity politics—but it also extends to political identity. These tactics draw on longstanding strategies to exploit difference and fracture liberation movements.

For example, during a Palestine solidarity rally in late 2023, when I was campaigning for city council, I proudly wore a DSA Santa Cruz t-shirt that read “Socializm” and a keffiyeh, a symbol of Palestinian resistance, to a rally. A seemingly friendly person rode up to me on her bike, asking to see my shirt. Assuming we shared a common cause, I naively grinned and showed it to her. Instead, she snapped a photo of me, accused me of intellectual property theft, and sped off. It turned out she’s a longtime, close friend and supporter of my political opponent at the time.

Within hours, another vocal supporter of my opponent—a prominent real estate figure and loud voice on NextDoor—posted the photograph with a plea not to vote for "law-flouters" like me. The post quickly circulated, using my visible solidarity with Palestine and my socialist political identity to discredit my campaign. During the months-long public debate surrounding a city council resolution calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, the rhetoric became increasingly volatile and deeply personal. Another prominent supporter of my opponent accused me of antisemitism in the comments of an Instagram post where I had called for supporting the resolution, and this charge was taken up by others.

These accusations weaponized my commitment to justice and solidarity with Palestine to attack my integrity and derail the conversation. The photo and my Instagram post were recirculated, cross-linked, and reposted several times, alongside other posts and comments about my house, my body, my family, and my personal and professional background. This backlash pollination across the local social media ecosystem created a sustained wave of hostility that felt both deeply personal and strategically targeted.

I alternated between trying to engage productively, reporting and blocking accounts, and ignoring the attacks altogether. It’s such a time and energy suck to engage, and in some ways, I think the people posting make themselves look worse than me. Still, it’s hard not to feel maligned by the community and gaslit when subjected to this behavior—all while being maliciously accused of “divisiveness” for holding different political views or fighting for liberation and justice. It can be exhausting and disheartening.

These experiences reflect a larger pattern of how identity politics and solidarity are manipulated to silence dissent and discredit individuals fighting for systemic change. By framing visible markers of solidarity—whether a keffiyeh, a t-shirt, or a social media post—as evidence of extremism or bigotry, these tactics shift focus away from the urgent issues at hand and create unnecessary divisions within movements. The deliberate framing of trans rights, racial equity, or calls for peace as “radical” similarly serves to fracture coalitions and prevent meaningful progress.

To counter these divide and conquer tactics, we must reclaim frameworks like intersectionality and relational accountability as tools for systemic analysis and coalition-building. Instead of descending into essentialism or deferring to identity-based authority alone, we can use these practices to strengthen our shared values and goals, resisting the forces that seek to divide us.

“We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.” – Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977

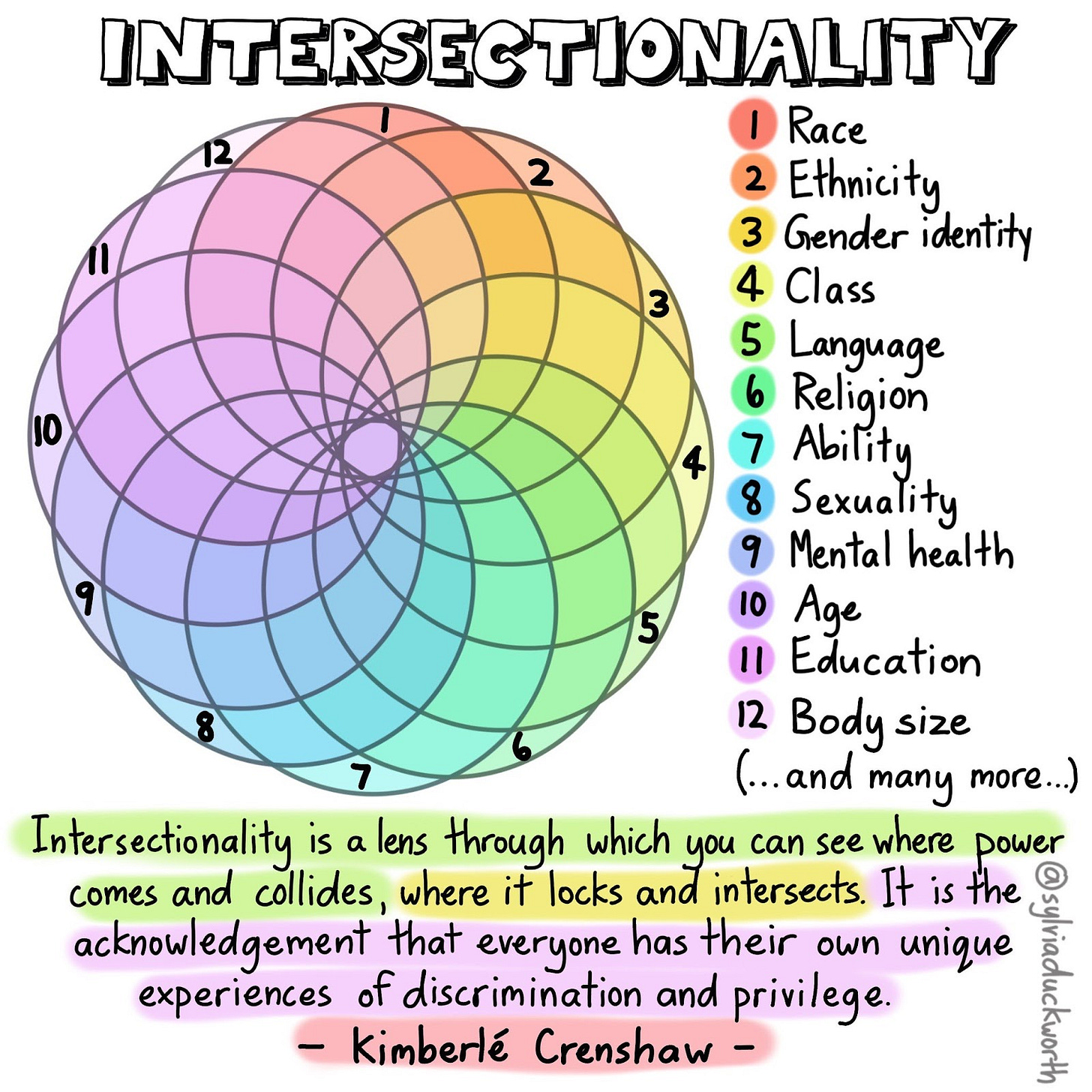

The concept of identity politics, first articulated as “interlocking” by the Combahee River Collective and expanded into a theory of intersectionality by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, provides powerful tools to understand and confront systemic oppression. These frameworks aren’t just about identity—they’re about analysis. They help us see how race, gender, class, and other axes of oppression overlap, connect, and accumulate to shape lived experiences and systemic barriers.

Crenshaw describes intersectionality as “a metaphor for understanding the ways that multiple forms of inequality or disadvantage sometimes compound themselves and create obstacles that are not understood within conventional ways of thinking about anti-racism or feminism.” She highlights the pitfalls of identity politics when it overlooks differences within groups, warning that this can lead to tension and frustrate efforts to address systemic issues.

Intersectionality shifts the focus from individual identities to the systemic hierarchies that create privilege and compound harm. It asks us to craft organizing strategies that uplift those most marginalized while remaining inclusive and responsive. As Rinku Sen reminds us, “the standard isn’t how intersectional is your identity, but how intersectional is your analysis.” This lens isn’t just anti-racist or anti-sexist; it is inherently anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist.

Barbara Smith, reflecting on the Combahee River Collective, underscores this point: “Anticapitalism is what gives it the sharpness, the edge, the thoroughness, the revolutionary potential.” This clarity ensures that intersectionality remains a tool for transformative action, not just a theoretical framework.

At the same time, Crenshaw warns against misreading social categories. She argues that categories like race or gender are socially constructed but have real significance in our world. “Categories have meaning and consequences,” she states, and the project for marginalized people is to “unveil the processes of subordination and the various ways those processes are experienced by people who are subordinated and people who are privileged.”

Crenshaw’s call to “occupy and defend a politics of social location” rather than abandon it is as relevant today as it was 33 years ago. Embracing our complex identities as a foundation for coalition-building and transformative action offers a powerful resistance strategy against forces that seek to divide and weaken movements for justice.

Stay Tuned for Part 2: Intersectionality in Action

In the next installment, we’ll explore how intersectionality moves from theory to practice, examining its role in relational accountability, coalition-building, and transformative organizing. I’ll share practical tools like power mapping and community agreements, and reflect on my experiences navigating demographic-specific work and inclusive coalitions.

Resources/Links

Glossary

Back to top

Anti-Capitalism: Opposition to systems prioritizing profit over people, emphasizing equitable resource distribution and workers’ rights.

Anti-Imperialism: Resistance to political, economic, or cultural domination by one nation over another.

Deference Politics: The practice of prioritizing the voices and leadership of marginalized individuals based solely on their identities. While intended to correct historical exclusion, over-reliance on deference politics can stifle critique and relational accountability.

Elite Capture: When powerful groups hijack social justice rhetoric to maintain dominance rather than dismantling oppression.

Essentialism: The belief that certain characteristics, behaviors, or identities are innate, fixed, and universal. In the context of social justice, essentialism often oversimplifies identity categories, ignoring the diversity and complexity within them.

Identity Politics: Political analysis and action based on the experiences and needs of marginalized groups, first articulated by the Combahee River Collective.

Identitarianism: A rigid focus on identity that reduces individuals to fixed categories, often at the expense of systemic analysis or coalition-building. Identitarianism is currently manifesting as white supremecist, nationalist movements.

Intersectionality: A framework coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw to analyze how overlapping systems of oppression shape lived experiences and systemic barriers.

Structural Intersectionality: The ways in which overlapping systems of oppression—like racism, sexism, and economic inequality—compound to create unique barriers for individuals within marginalized groups.

Political Intersectionality: The recognition that individuals’ identities often place them at the intersection of multiple political struggles, requiring movements to address overlapping and sometimes conflicting needs and priorities.

Liberal/Liberalism: A political philosophy that emphasizes individual rights, free markets, and representative democracy. In the U.S., liberalism often refers to centrist policies that focus on reforming, rather than dismantling, systemic inequalities.

Liberal Identity Politics: A form of identity politics co-opted by liberalism, focusing on representation over systemic change. Identity is used to uphold capitalism, rather than systemic change and universal liberation.

Positionality: The recognition of how an individual’s social identities (e.g., race, class, gender) and power dynamics shape their perspective, experiences, and interactions within systems of oppression and privilege.

Relational Accountability: Shared responsibility for maintaining trust, care, and integrity in relationships, ensuring solidarity and mutual respect.

Self/Co-Regulation: Balancing emotional responses for individual or collective productivity in organizing spaces.

Transformative Organizing: A framework for social change that integrates systemic critique, relational accountability, and care to build sustainable, inclusive movements aimed at dismantling oppression and creating liberatory alternatives.

I understand this concept but I have trouble imagining a concrete example, how that plays out. For instance, a situation that happens without applying the principles of intersectionality and the same where they are applied. Could you give us one? Thank you.